FROM MECHANISMS

TO FUNCTIONS

Research by

Kyriacos Kareklas

and Colleagues

Discussions on our most recent findings with frequent updates on our peer-reviewed and published research.

Topics: personality, individual plasticity, spatial memory, learning, collective behaviour & cognition, lateralised sensing, contest behaviour, assessment strategy, noise pollution, parental behaviour, sociality, motivation, cognition, neural circuitry, fear, attention, autism

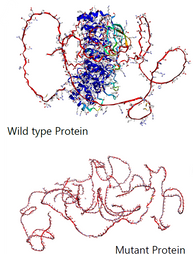

The use of animal models to uncover the gentic bases of brain and behaviour disorders is common, but behavioural assessment are limited to very simple characterizations. For complex pathologies, like autism, this limits the potential of animal models. Social contagion is a complex phenotype forming the basis of human empathic behaviour and involves attention to the behaviour of others for recognizing and sharing their emotional state. As such, It is a form of social emotion communication, which is the most common developmental impairment of autism spectrum disorders. We develped a zebrafish genetic model with mutations to a gene necessary for the production of the shank3 protein, which is necessary for the dveelopment of synapses and a candidate genetic factor for autism. The mutation reduced social contagion via deficits in attention which restricted the recognition of fear in others . The mutation aslo changed the expression of neuronal plasticity genes, which contributed specifically to the variation in attention. This shows a causal link between the ASD-associated gene and the attentional control of fear recognition and contagion. This addresses the ongoing scientific debate that attentional-deficit mechanisms account for emotion recognition difficulties in autistic individuals.

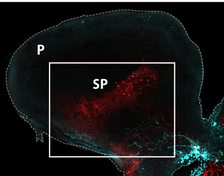

Emotional contagion, where individuals share and repeat the fear expression of other, is a basic form of empathy that also occures in fishes. In a recent study, we found that the neuropeptide oxytocin and its effects ofn specific brain regions are responsible for these behaviors in zebrafish, as they are in mammals. We also found that the mechanisms controls the sharing of fear by driving the recognition of that state, compared to other states, similar to its function in humans. These homologies between fish and mammals indicate that this basal empathic behaviour may have evolved many millions of years ago.

Sociality relies on the motivation to be with others and the ability to recognise them. These two aspects may have evolved independently, or linked by a shared evolutionary history that contributes to overall social competence. Altenatively, these aspects may not be specific to social capacities, but gneralised for asocial and non-social contexts. We used zebrafish to test if the motivational and cognitive components of social behavior are related and i specific for sociality or not. We found that the motivational (approach) and cognitive (recognition) components of sociality are only weekly associated and phenotypically linked to non-social traits, forming two general behavioral modules, suggesting that sociality traits have been co-opted from generalised traits. This was also supported by their genetic associations, since polymorphisms from a list of candidate “social” genes were associated with the motivational, but not with the cognitive component. This argues for general-domain motivational and cognitive behavioral modules in zebrafish, which have been co-opted for the social domain.

The drive to defend and use resources increases with their value and decreases with the costs of gaining them, including opponents. As such, changes in resource value due to the presence of humam disturbance will affect motivation based on contest costs and resource benefits. For male Siamese fighting fish territories are a key resource to be defended because they provide space to build bubble-nests for their offspring, which plays a significant role in reproductive success. So, the effects of external stressors on resource value can be identified in this species by measuring motivational changes in territorial defence and bubble-nest construction. We found that simulated human-activity noise reduced defense motivation when territory owners faced formidable opponents , but not when territories also contained bubble nests. In turn, nest-size decreased after contests under noise, but temporal nest-size changes relied also on opponents. Thus, the combined effects of noise are conditional on attainment costs and resource benefits. This demonstrates effects on resource value and shows how competition is affected under increasing anthropogenic activity.

Contests rely on the value of resources, but their outcome depends on fighting ability between contestants. Therefore, by assessing fighting ability, contestants can make better decisions to engage opponents or retreat. Yet, there is much about these assessments that we do not know. First, contestants may only assess their own ability or compare it to that of their opponents. Second, they might improve assessment over the course of a contest. We addressed these questions during territorial contests between male Siamese fighting fish and found that territory owners compare their ability to intruders when deciding to engage in fights and progressively improve their assessment. However, instead of avoiding more formidable opponents, they engaged them faster and increased their aggression towards them. This could be a startegy for protecting their parental legacy, because territory is primarily used to build bubble-nests for their offspring.

As springtime takes over, robins are increasingly using their song to communicate their aggressiveness and attain territory for breeding, but new evidence by our group shows that this may be difficult in noisy conditions.Typically information about a bird's aggressiveness is provided in the rate and magnitude of their song. However, the complexity of a song's acoustic structure can also harbour information. The study explores the role of song complexity for communicating aggressiveness and the impacts of its susceptibility to noise.

In the animal kingdom, competition for resources is common, and before getting in escalated injourious combat, it is common that contestants advertise their abilities. One way is to display these abilities, but another might be to detail them in communication. Similar to how a black-belt martial artist may verbalise her skill to opponents to ward them off, an aggressive bird may signal their intent in the structure of their song. Testing this in robins, we found that the complexity of their song's acoustic structure related to how eager they were to defend their territory (i.e. how fast to reply to an artificial provocation) and how aggressive their response was. Although the perception of this complexity also affcted how receivers responded, this was only true when no added noise was present. By manipulating background noise to acoustically resemble that of trafic, robins could not adjust their song based on the complexity of their opponents song. This raises concerns about the ability of birds to compete for resources under the growing extent of noise from human activities.

Lateralisation in humans and other vertebrates involves the input of sensory information more strongly to the brain hemisphere responsible for a required task. in humans and other vertebrates involves the input of sensory information more strongly to the brain hemisphere responsible for a required task. in humans and other vertebrates involves the input of sensory information more strongly to the brain hemisphere responsible for a required task. in humans and other vertebrates involves the input of sensory information more strongly to the brain hemisphere responsible for a required task. Examples include eye preference, and asymmetric inputs of sound and smell , which improve cognitive tasks when individuals process stimuli. Interestingly, the degree and direction of lateralisation can also vary between individuals depending on personality phenotype, which affects their behavioural responses towards stimuli. However, it is not known how sensory information is lateralised when processing stimuli and simultaneously organising a behavioural response towards them. In a recent study we show that this can be accomplished by separate senses being lateralised differently.

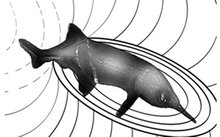

We demonstrate for the first time that the electrosensing of novel objects is lateralised in a weakly-electric fish and find that differences in the direction of laterality were attributed to whether a fish's personality promoted bolder or more timid approach tendencies towards unfamiliar objects. This is in contrast to visual laterality during inspection of novel objects, where a population level laterality was observed towards the left hemisphere similar to other fish. This species has a stronger representation of electrical than visual signals in its in its brain, which could drive the differences between senses in functional laterality. This novel observation reveals that different senses can be selected for lateralisation in different ways, likely depending on their dominance, which may have implications for the evolution and development of brain structure.

Individuals act differently under the same conditions; everyone can be either afraid of danger or brave in the face of risk, but to what degree varies. Some individuals are bolder and others more timid, but when they work as a group they benefit from reduced risk, better defense and collective detection of danger and resources. To achieve this individuals co-operate, collaborate and synchronise their actions. One way to do this is to assign ranks and have a hierarchical system, where some individuals lead and others follow. This is part of human and animal communities alike. Take for example military types of organisation and even political ones. An alternative is to opt for a democratic system, that relies on majority decisions (consensus), such as our electoral system. In human society both systems are interchangeable and fused, look at for example the merit-based hierarchy of private companies which coexists with shareholder and directorial consensus policy-voting. In animals, both systems can also arise depending on external conditions. To find food, a knowledgeable animal may lead others, but deciding between alternative food locations consensus will determine where the group will go. Alternatively, inter-group factors may also affect organisation, for instance the spread of directional changes when navigating relies on how close individuals are to perceive and pass the information. Could another internal factor be the degree in which individuals differ in their personality tendencies?

We found that the average personality of zebrafish individuals constituting a group and the degree of variation between them does not majorly affect their collective response. However, we also found that group behaviour at any situation reflected the average of individual behaviour at that same situation. Thus the adjustment of group actions to the average of its members is not generic, based on personality, but specific to current conditions. A consequence of the increased risk-taking in groups is that differences between individual and collective behaviour were greater for more timid individuals which might be a result of the safety-in numbers groups provide.

Like fish, humans are also a social vertebrate and we can possibly see how similar effects are responsible in how we collaborate: each individual compromises until agreement is reached, but the compromise is greater for animals which as individuals act most different than the agreed actions of the group. We found that that reaching this agreement can be difficult for very different individuals. Zebrafish groups composing individuals that varied most in their boldness, took longer to make a collective choice and were more likely to split. This suggests that when tendencies differ the most, strong-majority decisions are difficult to reach and groups are more likely to be divided, similar to the effects of polarised opinions in human society (see recent British referendum and American election results) .

We are often determined by our personality, a set of traits that develop during our lifetime and make us who we are. Our personalities can determine our actions and our emotions. Can they, however, determine how we process information? The way we assess our surroundings is intricately linked to how we feel and act. A typical pattern is that an unusual situation might impose fearfulness and stress, which can lead to the negative assessment of that situation and our active avoidance of it. However, an individual with a bolder personality is less likely to avoid and more likely to approach a novel situation, which could indicate a less pessimistic assessment. Recently, personality-based cognitive biases have been tested in animals, but mostly from the perspective of speed-accuracy trade-offs. These trade-offs propose that animals with bolder personalities are likely to make haste decisions; decisions which are faster but less accurate, making the learning process less successful. However, not all evidence shows such trade-offs. For example, bold guppies are faster at learning from others, but are not less accurate. This is because cognitive processing is complex, consisting of several interacting functions. Therefore effects may be limited to particular functions or affect some functions indirectly through others. Another factor couel be personality, which determines particular tendencies that can be intricately related to how individuals prioritise risk and reward, but also how they collect information , decide and make associations. For one, personality may influence information-collection, via levels of active exploration. In addition, more reward motivated personalities may be able to associate a reward to an act or a stimulus, e.g. food to locations, faster. In this new study on elephantnose fish, we show just that. Bolder fish, which exhibited higher levels of exploration and shorter approach tendencies to novel objects and food, also decided faster and were more accurate during training at reaching a food-rewarded location. As an indirect effect of their greater accuracy they also learned faster, which shows that indeed the explorative, reward-driven behaviour of bold fish predicts their cognitive performance in a spatial context. Therefore, by affecting our assessment and our behavioural response to risk and reward, personality also affects our ability to make associations related to risk and reward, and ultimately learn.

Human personality has fascinated us from early on. Aristotle, in his 'Nicomachean Ethics' identifies that humans "acquire a particular quality by constantly acting in a particular way... you become just by performing just actions, temperate by performing temperate actions, brave by performing brave actions.". Today personality in humans and animals is defined in an almost identical fashion, attributed by consistency in behavioral and emotional states. Our modern understanding is a resolution of evolved views corresponding to the parallel development of three fields: psychology, neuroscience and behavioural science. Findings by these fields share the understanding that temperament or personality is partly genetically inherited by next generations, but personality phenotypes develop during lifetime. Therefore, they are variable with conditions, experiences and changes in associated physiology.

The flexibility of personality, albeit more prominently supported in studies on humans, is now also at the forefront of animal behaviour studies. While the definitions applied in animal studies have been generally insistent on the consistency of phenotypes, animals require plasticity or flexibility in order to adapt to changes.

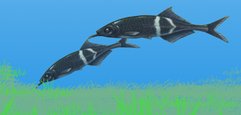

Peters' elephantnose fish can maintain sensing in light and dark conditions, perceiving shape, distance, size and electric properties of objects. They do this by producing their own weak electric signals which then interact with the environment and are sensed back, like sonar but with electric rather than sound waves. Their chosen environments in the Niger and Congo delta are dim or dark, and one adaptive explanation for this is that they can avoid visually orienting predators. In a recent study on this fascinating species we found that consistency in their level of boldness to approach and explore was only exhibited in the light, whereas in the dark all individuals, even those which were constantly timid in the light, behaved very boldly. As a consequence, the degree of change between light and dark was greater for those being more timid in the light. Conversely, those that were constantly bolder in the light simply maintained their level of boldness in the dark. This shows that bolder fish are at a disadvantage by remaining active in the risky bright conditions where they are conspicuous to predators, whereas timid fish prioritise safety when its risky and the location of resources only when its safe. To balance this disadvantage of bolder personalities, the flexibility of more timid animals is an energetically costly process. The trade-offs between the benefits and costs of each strategy, flexible or stable, can be resolved by the variable levels of flexibility/stability within populations. This process suggests that behavioral flexibility varies within populations and maintains trade-offs in selection.

This study demonstrates that personalities in animals, as in humans, can be flexible. However, individuals may indeed vary in this also, with some having more flexible personalities and others more constant ones. This opens new possibilities in how personality might be examined in the future.

Kyriacos Kareklas, 2023

All rights reserved